Day 48 習慣は「努力」ではなく「設計」でつくる Habits Are Built Not by Willpower, But by Design

[シリーズ構造] 柱E|癖にする

本稿では、良い習慣は「意志力」ではなく「設計」でつくられることを解説します。きっかけ・ルーチン・環境を意図的に整えることが、持続的な行動変容と判断習慣の強化につながります。

▶ シリーズ概要: シリーズ全体マップ:人間のしなやかさ ― サイバー判断力のために

▶ 柱E|習慣と自律 関連記事:

習慣は「努力」ではなく「設計」でつくる Habits Are Built Not by Willpower, But by Design

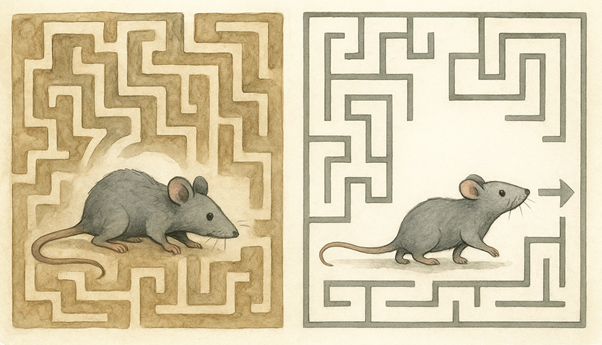

習慣は、呼び出すものではない。設計されるもの

多くの人は、習慣を

「意志の強さ」

「もっと頑張ること」

「自分を律し続けること。自己統制や自己管理」

の問題だと思っています。

気合いを入れて、自分に言い聞かせて、気を抜かないように注意し続ける。そうすれば、良い習慣は身につくはずだ、と。でも、科学はまったく違うことを示しています。

これまで私は、Gartnerの Cyber Judgment Framework、Andrew Likierman博士の「判断力」の理論、記憶システムの認知科学、心理学と文化が判断に与える影響を見てきました。そして、最後にどうしても戻ってきてしまう問いがありました。

どうすれば「良いサイバー判断」を、続くものにできるのか?

その答えは、とてもシンプルです。そして、とても見落とされがちな場所にあります。

それが 「習慣」 です。

なぜなら、本当に強いサイバー判断力とは、考えてから発動するものではなく、呼吸のように、自然に立ち上がるものでなければならないからです。

なぜ「習慣」がサイバー判断の欠けたピースなのか

多くのセキュリティ教育が間違えている点があります。それは、「人は必要なときに、ちゃんと判断を思い出してくれる」という前提に立っていることです。

でも、現実の仕事はそう動いていません。私たちは日々、メール、リンク、添付ファイル、ファイル共有、権限付与等々、何百もの小さな判断をしています。

しかもその大半は、考える前に、無意識で行われています。もし良いサイバー判断が「習慣」として身体に入っていなければ、本当に必要な瞬間には、まず出てきません。

思い出してみてください。最後にあなたの組織で行われたフィッシング訓練。最初の1週間、あるいは2週間。みんな少しだけ注意深くなる。

でも、その後は?

元に戻ります。

それは怠慢だからではありません。努力に依存した警戒は、続かないからです。

習慣とは、努力をしなくても、毎日ちゃんと現れる判断のこと。

行動を手続き記憶に移すことで、第5章で見た「速く、自律的な判断」を支えてくれます。ほんの小さな行動、立ち止まって確認する。すぐに報告する。その積み重ねが、

攻撃成功率を下げ、検知を早める。

ここで私は、昔読んだ一冊の本に立ち戻りました。Charles Duhigg『The Power of Habit(習慣の力)』を改めて読み返してみて、「これは、サイバーセキュリティの本なのでは?」と思うほど、核心を突いていました。

ただし、その前に一つ。なぜ従来のトレーニングが失敗し、なぜ習慣アプローチが機能するのか。そこを、はっきりさせておく必要があります。

受け入れがたい真実:意志力は、土台として弱すぎる

はっきり言います。

意志力は、有限です。

Baumeisterらの「エゴ消耗」の研究が示す通り、自己制御や集中力は、使えば減ります。

一日中、会議をして、判断をし続けて、調整をして、我慢をして、その状態で、夕方に届く一通のメール。

「至急:アカウント確認が必要です」

そこで意志力が負けるのは、弱いからではありません。もう、残っていないからです。

努力と注意力に依存したセキュリティは、砂で作った堤防のようなもの。

平時は保つ。でも、圧がかかれば崩れます。そして、サイバーの世界では圧は常にかかっている。

これが、啓発キャンペーンが消える理由。研修効果が薄れる理由。「分かっていたはずの人」が引っかかる理由です。

問うべきなのは、「どうすればもっと頑張らせられるか」ではありません。

「どう設計すれば、努力しなくても正しい選択ができるか」です。

努力から構造へ:発想の転換

ここで、すべてが変わります。

「どうすれば人にもっと注意させられるか?」ではなく、

- どうすれば、安全な行動が一番楽な道になるか

- どうすれば、判断が自動的に立ち上がれる流れを作れるか

- どうすれば、正しい選択が最も簡単な選択になるか

を考える。

これが、努力ベースから、構造ベースへの転換です。

ThalerとSunsteinはこれを「選択アーキテクチャ(Choice Architecture)」と呼びました。人を縛らなくても、意志力を要求しなくても、設計だけで行動は変えられる。

サイバーセキュリティにおいては、例えば:

- セキュア設定がデフォルトである

- ワークフローに自然に確認が入る

- 怪しい挙動がすぐ可視化される

- 危険に進むより、相談する方が簡単

人を変えようとしているのではありません。環境を変えているのです。

構造と個人をつなぐもの:Adaptive Learning(個別最適化された学習)

ここで重要になるのが Adaptive Learning です。単なる新しい研修手法ではありません。知識を、個人ごとの「無意識の習慣」に変える装置です。

従来の研修は、「全員に、同じ内容を、同じペースで」という致命的な前提に立っています。Adaptive Learningは違います。

人ごとに、必要な量、必要な文脈、必要なタイミングを変えます。

財務で毎日支払いメールを見るSarahと、権限管理が中心のIT担当Michael。同じ訓練を与えるのは、合理的でしょうか?

Adaptive Learningは、習慣が最短距離で定着する足場を作ります。

私が組織で見てきた中で、ある企業は年次研修から文脈特化型のアダプティブ学習に切り替え、フィッシング被害率を73%削減しました。意志力が強くなったからではありません。構造が、人に合っただけです。

習慣アーキテクチャへ

Adaptive Learningは、習慣形成の一部です。でも、全体ではありません。最終的に必要なのは、何が引き金になるのか、どんな行動を自動化するのか、何が強化として働くのか。この問いに、驚くほど明快に答えてくれるのがDuhiggの「習慣ループ」です。

明日は、Cue - Routine - Reward の構造をサイバーセキュリティにどう落とし込むか。「判断の習慣」 をどう設計するかを掘り下げます。

最後に、習慣は、根性では作れない。習慣は、設計で作られます。

優れたセキュリティ組織は、人に「もっと頑張れ」とは言いません。自然に、安全な行動が出てくる構造を作ります。それが、コンプライアンスとしてのセキュリティから、

組織能力としてのセキュリティへの転換点です。人は最弱リンクではありません。正しく設計すれば、最も適応力が高く、学習し、強くなる防御層です。

- 意志力は消耗する。構造は残る。努力に依存したセキュリティは続かない。安全行動が最短ルートになる設計を。

- Adaptive Learningは、知識と習慣をつなぐ橋。文脈・個人・タイミングに適応して初めて、判断は自動化される。

- 習慣こそが判断の配送装置。問いは「判断できるか」ではなく、「必要な瞬間に、自動で出てくるか」

------

[Series Structure] Pillar E | The Science of Making Good Judgment a Habit

This article explains that good habits aren't created by willpower but by intentional design. It shows how structuring cues, routines, and environments -- not sheer effort -- leads to lasting behavioral change and stronger judgment habits.

▶ Series overview: Series Map -- Human Flexibility for Cyber Judgment

▶ Other posts in Pillar E (Habit & Autonomy):

- Day 47 | The Science of Making Good Judgment a Habit

- Day 48 | Habits Are Built Not by Willpower, But by Design

Habits Are Structured, Not Summoned

Most people think habits are about willpower. About trying harder. About discipline.

But science tells a different story.

After exploring Gartner's Cyber Judgment Framework, diving into Dr. Andrew Likierman's theory of judgment, understanding the cognitive science behind memory systems, and recognizing the profound impact of psychology and culture, I found myself returning to a single, essential question:

How do we make good cyber judgment stick?

The answer lies in understanding and leveraging the most powerful driver of lasting behavioral change--habit formation. Because ultimately, exceptional cyber judgment must become as automatic and reliable as breathing.

Why Habits Are the Missing Link in Cyber Judgment

Here's what most cybersecurity training gets wrong: it treats judgment as something people will consciously remember to use when needed.

But that's not how our days actually unfold.

In our real work lives, we make hundreds of micro-judgements about emails, links, file sharing, and system access--most of them automatically, without deliberate thought. If good cyber judgment isn't embedded as habitual behavior, it simply won't happen when it matters most.

Think about the last phishing awareness campaign your organization ran. Employees were vigilant for a week, maybe two. Then what? They returned to their default behaviors. Not because they're careless. Because effort-based vigilance is unsustainable.

Habits are how good judgment shows up every day without extra effort.

They reduce cognitive load by moving behaviors into procedural memory, which supports the fast, autonomous judgment we explored in Chapter 5. In cybersecurity, small, consistent behaviors--like pause-and-verify routines or immediate suspicious activity reporting--compound into dramatically fewer successful attacks and faster threat detection.

This realization brought me back to a book I had read years ago: "The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business" by Charles Duhigg.

Revisiting it, I was reminded of how clearly Duhigg explains the mechanics of habit and how profoundly his framework applies to cybersecurity. But before we dive into his framework tomorrow, we need to understand something fundamental about why traditional training fails and why habit-based approaches succeed.

The Uncomfortable Truth: Willpower Is a Terrible Foundation

Let me say this plainly: Willpower is a finite resource that depletes throughout the day.

The research is clear. Baumeister and colleagues' seminal work on ego depletion demonstrated that self-control draws from a limited pool of mental energy. When we exhaust that pool through constant decision-making and self-regulation, our capacity for further self-control diminishes--sometimes dramatically.

Relying on effort and conscious judgement for cybersecurity behaviors is like building a dam out of sand. It works until pressure hits.

And in cybersecurity, pressure is constant.

We're tired after back-to-back meetings. We're rushing to meet a deadline. We've already made a hundred small judgements that day. Then an email arrives: "Urgent: Verify your account now." In that moment, willpower fails. Not because we're weak. Because the well has run dry.

This is why awareness campaigns fade. Why training effects decay. Why even well-intentioned people fall for phishing attacks they "should have" spotted.

The fundamental question isn't "How do we make people try harder?"

It's "How do we design systems where the right choice requires no effort at all?"

From Effort to Structure: The Paradigm Shift

Here's the shift that changes everything:

Instead of asking "How can we make people work harder to spot threats?"

We ask:

- "How can we design their environment so secure behavior is the path of least resistance?"

- "How can we structure their workflow so good judgment becomes automatic?"

- "How can we build systems where the right choice is also the easiest choice?"

This is the fundamental shift from effort-based thinking to structure-based thinking.

Thaler and Sunstein call this "choice architecture" in their work on nudges--the idea that how choices are structured and presented matters enormously. Small design changes can produce large behavioral effects without forbidding options or requiring willpower.

In cybersecurity, this means:

- Default settings that are secure (not opt-in security)

- Workflows that naturally include verification steps

- Systems that make suspicious activity immediately visible

- Environments where asking for help is easier than proceeding unsafely

We're not asking people to be different. We're designing environments that make secure behavior natural.

Adaptive Learning: How Structure Meets the Individual

This is where adaptive learning becomes crucial--not as another training methodology, but as the mechanism that transforms conscious knowledge into unconscious habit for each specific person.

Traditional training operates on a tragic assumption: that everyone needs the same thing, at the same pace, in the same way. It's the educational equivalent of prescribing the same medicine, same dosage, to every patient regardless of their condition.

Adaptive learning works differently. It continuously adjusts to individual performance, creating personalized pathways.

Think about it this way: Sarah in Finance handles payment authorization emails dozens of times per day. Michael in IT rarely touches financial workflows but constantly deals with system access requests. Traditional training gives them identical phishing scenarios. Adaptive learning gives Sarah intense practice with payment fraud patterns and Michael with privilege escalation social engineering.

The key insight: Adaptive learning creates the scaffolding that allows habits to form efficiently for each individual.

It identifies the minimal effective dose of practice needed for each person, eliminates wasted effort on already-mastered concepts, and concentrates reinforcement where it's needed most.

In my experience working with organizations on cyber judgment, I've seen this distinction matter enormously. When training adapts to:

- Where people actually are(not where we assume they are): Rather than starting from zero, adaptive systems assess current behavioral patterns and knowledge gaps, building on existing foundations.

- How people actually learn(not how curricula are structured): The goal isn't to "finish" the training module but to achieve lasting behavioral change. Adaptive systems use spaced repetition, retrieval practice, and progressive challenge to move knowledge from short-term awareness to long-term procedural memory.

- What people actually do(not generic scenarios): Instead of abstract examples, adaptive systems present challenges that mirror an individual's actual work context--the specific applications they use, the types of data they handle, the communication patterns they follow.

- When people actually need it(not on an annual schedule): Adaptive learning doesn't end when the module completes. It provides just-in-time micro-interventions when behavioral data suggests old patterns are re-emerging.

The difference is night and day. One organization I worked with saw their phishing click rates drop by 73% when they shifted from annual compliance training to adaptive, context-specific micro-learning. Not because people suddenly had more willpower. Because the structure met them where they were.

From Adaptive Learning to Habit Architecture

Adaptive learning provides the personalized repetition and context needed for habit formation. But it's still only one piece of the puzzle.

The complete picture requires understanding:

- What triggers secure behaviors?

- What routines need to become automatic?

- What rewards reinforce these behaviors?

These are the questions that Charles Duhigg's habit framework answers with remarkable clarity. His research reveals the underlying mechanics of how habits form, persist, and can be intentionally designed.

Tomorrow, we'll dive deep into Duhigg's Habit Loop framework--the cue-routine-reward cycle that governs all habitual behavior. We'll explore how this framework can be applied specifically to cybersecurity, creating what I call "judgment habits": automatic, context-appropriate security behaviors that require minimal cognitive effort but deliver maximum protection.

For now, remember this core principle:

Habits aren't built through heroic effort. They're built through intelligent design.

The most effective cybersecurity programs don't ask people to work harder--they architect environments, workflows, and reinforcement systems that make secure behavior the natural, automatic choice.

This is the shift from cybersecurity as a compliance burden to cybersecurity as an embedded organizational capability. And it starts with understanding that the human element isn't the weakest link--it's the most adaptable, trainable, and powerful defense system we have, if we design for how humans actually work.

Wrap up

- Willpower depletes; structure endures: Research on ego depletion shows that relying on conscious effort for security behaviors is fundamentally unsustainable. Design environments where secure behavior is the path of least resistance.

- Adaptive learning bridges knowledge and habit: Personalized, context-specific practice moves security knowledge from conscious awareness to automatic procedural memory--but only when it adapts to each individual's actual work context and learning pace.

- Habits are the delivery mechanism for judgment: Good cyber judgment must become habitual to function reliably under pressure and cognitive load. The question isn't "Can people judge well?" but "Will they, automatically, when it matters?"

References 出典・参照

Core Habit Formation and Behavior Change

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252-1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2024). Self-control and limited willpower: Current status of ego depletion theory and research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 58, 101863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101863

Duhigg, C. (2012). The power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. Random House.

Graybiel, A. M. (2008). Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31, 359-387. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112851

Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998-1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Smith, K. S., & Graybiel, A. M. (2016). Habit formation. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 18(1), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/ksmith

Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 289-314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Procedural Memory and Automaticity

Anderson, J. R. (1982). Acquisition of cognitive skill. Psychological Review, 89(4), 369-406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.89.4.369

Fitts, P. M., & Posner, M. I. (1967). Human performance. Brooks/Cole.

Seger, C. A. (2008). How do the basal ganglia contribute to categorization? Their roles in generalization, response selection, and learning via feedback. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(2), 265-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.07.010

Squire, L. R., & Dede, A. J. O. (2015). Conscious and unconscious memory systems. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(3), a021667. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021667

Adaptive Learning and Personalized Education

Brinton, C. G., & Chiang, M. (2015). MOOC performance prediction via clickstream data and social learning networks. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM) (pp. 2299-2307). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/INFOCOM.2015.7218617

Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2017). Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers & Education, 104, 18-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.10.001

Walkington, C., & Bernacki, M. L. (2020). Appraising research on personalized learning: Definitions, theoretical alignment, advancements, and future directions. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(3), 235-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1747757

Xie, H., Chu, H.-C., Hwang, G.-J., & Wang, C.-C. (2019). Trends and development in technology-enhanced adaptive/personalized learning: A systematic review of journal publications from 2007 to 2017. Computers & Education, 140, 103599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103599

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education - where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Cybersecurity Training Effectiveness and Failure

Canfield, C. I., Fischhoff, B., & Davis, A. (2016). Quantifying phishing susceptibility for detection and behavior decisions. Human Factors, 58(8), 1158-1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720816665025

Ho, G., Cidon, A., Gavish, L., Schweighauser, M., Paxson, V., Savage, S., Warfield, A., & Wagner, D. (2024). "That wasn't a good idea to open that": Understanding employee responses to embedded phishing training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.16285. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.16285

Huntress. (2024). 2024 human risk report: The state of security awareness training. https://www.huntress.com/resources/2024-human-risk-report

Kumaraguru, P., Sheng, S., Acquisti, A., Cranor, L. F., & Hong, J. (2010). Teaching Johnny not to fall for phish. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology, 10(2), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1145/1754393.1754396

Ussher-Eke, D. (2023). From awareness to action: Designing effective cybersecurity training programs. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 11(2), 494-504. https://doi.org/10.30574/ijsra.2023.11.2.0133

Wash, R., & Cooper, M. M. (2018). Who provides phishing training? Facts, stories, and people like me. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Paper No. 492). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174066

Choice Architecture and Behavioral Design

Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338-1339. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091721

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R., & Balz, J. P. (2013). Choice architecture. In E. Shafir (Ed.), The behavioral foundations of public policy (pp. 428-439). Princeton University Press.

Cognitive Load and Decision-Making Under Stress

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 261-292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5

Spaced Repetition and Memory Consolidation

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354-380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.354

Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

Dreyfus Model (Referenced from Previous Chapter)

Dreyfus, S. E., & Dreyfus, H. L. (1980). A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Unpublished report supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFSC), University of California at Berkeley.

Tiny Experiments Framework (Referenced from Day 15)

Le Cunff, A.-L. (2023). Tiny experiments: How to live freely in a goal-obsessed world. Portfolio.